Symposium 2024 - 2025

“Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections”

“Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections”

Watch the presentation

Professor Alex Guerrero - Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University. Professor Guerrero works on political philosophy, ethics, legal philosophy, and epistemology with research and teaching interests in Native American and Indigenous Philosophy, Mesoamerican Philosophy, Chinese Philosophy, Latin American Philosophy, and African Philosophy, among other areas.

Abstract: Democracy is in trouble. What is going wrong? The first part of the talk argues that, perhaps surprisingly, the problem is with the heart of modern democracy: the election. Elections are failing as accountability mechanisms. Elections provide powerful short-term incentives, leading elected politicians to downplay long-term catastrophic concerns. Elections create division where none need exist. Elections and elected officials are easily bought off and captured by the elite. The most powerful among us take advantage of this to control who is elected, what policies are enacted, and which problems are ignored. As a result, modern electoral democracies are often incapable of helping us solve the urgent problems we face. What should we do? The second part of the talk introduces a radically new form of democracy: lottocracy. Lottocratic systems include many new elements, but the most striking is the shift from using elected representatives to using representatives selected through lottery. I introduce lottocratic systems, their potential advantages, and potential concerns. The argument engages with foundational philosophical questions, considering how rights of political participation, political equality, political power, considerations of accountability and legitimacy, and the nature of democracy itself are illuminated and reconfigured once we move past the electoral representative framework.

Symposium 2023-2024

"True Grit: Striving in the Face of Adversity"

"True Grit: Striving in the Face of Adversity"

Watch the Presentation

Jennifer Morton - Presidential Associate Professor of Philosophy

at the University of Pennsylvania. Research spans ethics, political

and moral philosophy, and the philosophy of education.

Abstract: It's common to set out on a challenging pursuit without knowing whether you will succeed. As we confront hurdles and setbacks, we face a crucial decision: give up, or persevere? Optimism about our chances can help us avoid giving into premature despair. But we argue that "grit"—striving in the face of adversity—can be rational only when it doesn't turn into Pollyannaish optimism. To strive rationally, we also need to pay close attention to our abilities and strengths, as well as to whether our circumstances will be conducive to our success. We develop a model of striving that aims to capture the multifaceted nature of this critical capacity of agents.

Symposium 2021 - 2022

“How Can Procreation be Permissible?”

“How Can Procreation be Permissible?”

Watch the presentation

Professor Jeff McMahan - White's Professor of Moral Philosophy at Oxford University

Distinguished research fellow at the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics

Fellow of Corpus Christi College

Abstract: Most people believe that the expectation that a person would have a life worth living does not in itself provide a moral reason to cause that person to exist. Most of us also believe that there is a moral presumption against inflicting a harm on a person even if in doing so one would confer on that person a benefit of equal or even somewhat greater magnitude. We also accept that there is a presumption against any act that risks causing a person to have a miserable life. Taken together, however, these claims seem to imply that there is a moral presumption against procreation. For in choosing to have a child, one causes the conditions in which the child will inevitably suffer harms and one also risks creating a person whose life will be miserable. Although there is a high probability that the harms will be outweighed by benefits, so that the life will be well worth living, most believe, as I noted, that these considerations are not reasons in favor of having a child that weigh against the reasons just cited not to have a child. Hence the question in the title. Is procreation morally justifiable only when the interests of existing people – in particular, potential parents – override the moral objections to procreation? Or might a small risk of a miserable life be morally offset by a high probability of a good life? And might a small number of miserable lives be morally offset by a sufficiently large number of good lives?

Symposium 2019 - 2020

"Climate Change, Justice, and Quality of Life:

"Climate Change, Justice, and Quality of Life:

A Convenient Truth … and a Lesson from COVID-19?"

Watch the presentation

Professor Peter Railton - University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Gregory S. Kavka Distinguished University Professor and

John Stephenson Perrin Professor of Philosophy

Abstract: Justice would appear to require that those who are the principal beneficiaries of a history of economic and political behavior that has resulted in dramatic climate change, and whose societies have contributed most heavily to causing this change, should bear a correspondingly large share of the costs of contending with the problems such change is creating for populations worldwide. At the same time, however, a prevalent material conception of happiness holds that this would require sacrificing the “quality of life” enjoyed in the most-developed countries. Such sacrifice seems unlikely to achieve sufficient social and political support in these countries. However, there are good reasons for doubting the material conception of “quality of life”. A large body of social science research into the nature and sources of “subjective well-being”—a measure of how people experience and evaluate their lives—suggests that more sustainable levels of resource utilization and greater equity in distribution could be achieved without great sacrifice to “quality of life” in the most-developed countries, and in ways that could significantly enhance subjective well-being in the less-developed countries. This I call a “convenient truth”. The varied social responses to the COVID-19 pandemic suggest this as well: there can be wide differences in outcomes in terms of well-being and justice that are not simply a function of a society’s material wealth, and where significant gains can be achieved without significant sacrifice to quality of life.

"CRISPR and the World: Little Worry, Too Much Worry, and Not Enough Worry"

"CRISPR and the World: Little Worry, Too Much Worry, and Not Enough Worry"

Watch the presentation

Henry T. (Hank) Greely - Dean F. and Kate Edelman Johnson Professor of Law and, Professor, by courtesy, of Genetics Stanford Law School

Abstract: CRISPR is a remarkable, multifaceted tool with vast applications to bioscience research. It also, even in just its genome editing uses, big implications for the world. Those implications, however, vary tremendously in ways that “the world” does not seem to appreciate. This talk will discuss some uses of CRISPR, such as in somatic cell therapy, that, although potentially very important, raise few or no new ethical or social issues. It will then discuss one application of CRISPR, human germline genome editing, that has raised tremendous controversy but seems unlikely to be, ultimately, very important. Finally, it will address the use of CRISPR to modify non-human organisms. This is likely to be its most significant use but has received far too little attention.

"Selves Like us"

"Selves Like us"

Susan R. Wolf - Professor of Moral Philosophy and Philosopher of Action, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Abstract: Since at least the seventeenth century, philosophers have distinguished membership in the species homo sapiens from moral personhood, a category which they take to be of considerable ethical and practical significance. But there are other nonbiological features that are of ethical and practical significance as well, suggesting that there is an ethical, non-biological conception of humanity that is different from the standard philosophical understanding of moral personhood. After reflecting on the benefits and dangers of focusing attention on the idea of “the distinctively human,” the lecture explores the variety of features and capacities that distinguish “selves like us” from lower animals, artificially intelligent machines, and possibly imaginary divine and extra-terrestrial rational individuals.

Symposium 2018 - 2019

"Immigration and Morality: Invitation to a Dialogue"

"Immigration and Morality: Invitation to a Dialogue"

Joseph Carens - Professor of Political Science, University of Toronto

Abstract: In this talk, I want to invite those in the audience to set aside partisan political concerns and even their own immediate interests for a short time and to reflect upon the ways in which immigration raises questions about our most fundamental moral values, about what we think is right and wrong, just and unjust. I will provide a brief overview of the range of moral questions that are raised by immigration, but I’ll focus mainly on three particularly controversial ones: What should we do about irregular migrants (i.e., immigrants who have settled without official authorization)? What are our responsibilities towards refugees?

Finally, are we really entitled to control immigration at all or should borders be generally open? I will offer some challenging views on these questions, but my hope is that whether those who attend agree with me or not, they will experience what I say as an invitation to think more deeply about this important topic and perhaps to talk with people with whom they disagree.

"Condemned to Tribalism? Us Versus Them in Contemporary America"

"Condemned to Tribalism? Us Versus Them in Contemporary America"

Allen Buchanan - Professor of Philosophy at Duke University and also a professor of the Philosophy of International Law at the Dickson Poon School of Law at King's College, London

Abstract: Many people are aware that in the U.S. at present there is an increase in “tribalism” but there is much unclarity about what “tribalism” is. In this presentation, I contrast tribalistic or exclusive moralities with inclusive ones. I first argue that the standard evolutionary story about how human morality originated among our remote ancestors between 1.8 million and 10,000 years ago suggests to many people that we are condemned to tribalism, that humans are “hard-wired” by evolution to have exclusive moralities, moralities that relegate “outgroup” people to an inferior status. I then argue for a revisionist account of the evolutionary origins of morality according to which humans have an adaptively plastic moral capacity: in certain environments, tribalistic or exclusive moral responses will dominate, but in different environments a more inclusive moral orientation is possible.

I explain how morality, for many people, has become more inclusive during the last 300 years, in some parts of the world, but argue that there is a new form of tribalism: intrasocietal tribalism, where the inferior, dangerous other is not thought of as a member of another society, but rather is a group within our society. I next show that this new form of tribalism threatens to undue the recent progress that some humans have made in developing a more inclusive moral orientation. I then explain how ideology, properly understood, creates this new kind of tribalism and who that ideology is an adaptation for cooperation in modern, complex societies in which there is a plurality of groups competing for economic, political, and cultural dominance.

Symposium 2017 - 2018

"#metoo and the Failure to Warn Others"

"#metoo and the Failure to Warn Others"

Professor Elizabeth Harman - Princeton University

Abstract: Many people are aware that in the U.S. at present there is an increase in “tribalism” but there is much unclarity about what “tribalism” is. In this presentation, I contrast tribalistic or exclusive moralities with inclusive ones. I first argue that the standard evolutionary story about how human morality originated among our remote ancestors between 1.8 million and 10,000 years ago suggests to many people that we are condemned to tribalism, that humans are “hard-wired” by evolution to have exclusive moralities, moralities that relegate “outgroup” people to an inferior status. I then argue for a revisionist account of the evolutionary origins of morality according to which humans have an adaptively plastic moral capacity: in certain environments, tribalistic or exclusive moral responses will dominate, but in different environments a more inclusive moral orientation is possible.

I explain how morality, for many people, has become more inclusive during the last 300 years, in some parts of the world, but argue that there is a new form of tribalism: intrasocietal tribalism, where the inferior, dangerous other is not thought of as a member of another society, but rather is a group within our society. I next show that this new form of tribalism threatens to undue the recent progress that some humans have made in developing a more inclusive moral orientation. I then explain how ideology, properly understood, creates this new kind of tribalism and who that ideology is an adaptation for cooperation in modern, complex societies in which there is a plurality of groups competing for economic, political, and cultural dominance.

"The Roads To and From the Paris Climate Agreement"

"The Roads To and From the Paris Climate Agreement"

Watch the presentation

Professor Andrew Light - University Professor of Philosophy, Public Policy, and Atmospheric Sciences at George Mason University, and Distinguished Senior Fellow in the Climate Program at the World Resources Institute, in Washington, D.C.

Abstract: In December 2015 over 190 countries met in Paris for the 21st meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change where they succeeded in creating a new international climate agreement. Many have heralded the outcome as a groundbreaking achievement for international diplomacy and global climate action. Others have argued that the climate commitments that parties brought to the table in Paris are ultimately too weak to achieve the agreements’ lofty aspirations. Whichever is true, the agreement is now undergoing an early and serious stress test with the announcement of the intended withdraw of the United States from the agreement. To better understand the significance of the Paris Agreement, and why it is worth fighting for its preservation, we will review the recent history of the UN climate negotiations, and how this outcome evolved from earlier failed attempts in this process, finally overcoming the immense hurdle of assigning responsibility for hitting global mitigation targets. From there we will look at what the future holds for global climate cooperation, including new opportunities for enhanced climate action.

Symposium 2016 - 2017

“Death Squads and Death Lists: Targeted Killing and the Character of the State”

“Death Squads and Death Lists: Targeted Killing and the Character of the State”

Watch the presentation

Professor Jeremy Waldron - University Professor and Professor of Law, New York University and formerly Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College, Oxford

Abstract: The intention of this lecture is to urge critical reflection upon current US practices of targeted killing by considering not just whether acts of targeted killing can be legally justified but also what sort of state we are turning into when we organize the use of lethal force in this way – maintaining a list of named enemies of the state who are to be eliminated in this way. I make use of the unpleasant terminology of "death lists" and "death squads" to jolt us into this reflection. Of course, there are differences between the activities of death squads in (say) El Salvador in the early 1980s and the processes by which US special forces, intelligence personnel, and drone operators, kill the individuals named on a list of state enemies, one by one. They are not morally equivalent. But the two sets of phenomena are much closer to one another than we ought to be comfortable with. And we certainly should not be comfortable with a world in which death lists and death squads -- even of the respectable American kind -- become a standard practice and standard operating procedure for all states.

"The Shape of the State"

"The Shape of the State"

Watch the presentation

Philip Pettit - L.S. Rockefeller University Professor of Politics and Human Values at Princeton University

Abstract: Political philosophy is an account of what the polity or state ought to be and ought to do. But what it ought to be and do depends on the shape it can assume. And that is the topic of this lecture. The questions to be raised include the relation of the polity to the legal system, its role as a corporate agency, the locus of sovereignty within that agency, and the different democratic modes in which it may be organized.

Symposium 2014 - 2015

"Consciousness Unbound: The Ethics of Neuroimaging After Severe Brain Injury”

"Consciousness Unbound: The Ethics of Neuroimaging After Severe Brain Injury”

Watch the presentation

Charles Weijer, M.D., Ph.D. - Professor of Philosophy, University of Western Ontario

Abstract: Severe brain injury is a major cause of disability and death. In the hours and days after brain injury, families may be faced with the decision of whether to continue life-sustaining therapy. Patients who survive may emerge into a vegetative or minimally conscious state in which they are incapable of meaningful communication. Recent advances in neuroimaging cast a new light on behaviorally non-responsive patients after brain injury. Functional MRI is now being used in the research setting to map residual cognitive function in brain-injured patients, including the ability to process speech, comprehend language, and follow commands. In a few cases, neuroimaging has allowed for communication with otherwise unresponsive patients. This research raises difficult ethical issues. Should research results be shared with families in the ICU setting when life and death decisions are at stake? What does neuroimaging data tell us about our moral obligations to brain-injured patients? And how can neuroimaging communication be used responsibly to benefit patients?

Symposium 2013 - 2014

“Peter Singer on Effective Altruism”

Peter Singer - Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics, Princeton University

"Can We Sustain Democracy, and the Planet Too?"

Philip Kitcher - Dewey Professor of Philosophy, Columbia University

Symposium 2012 - 2013

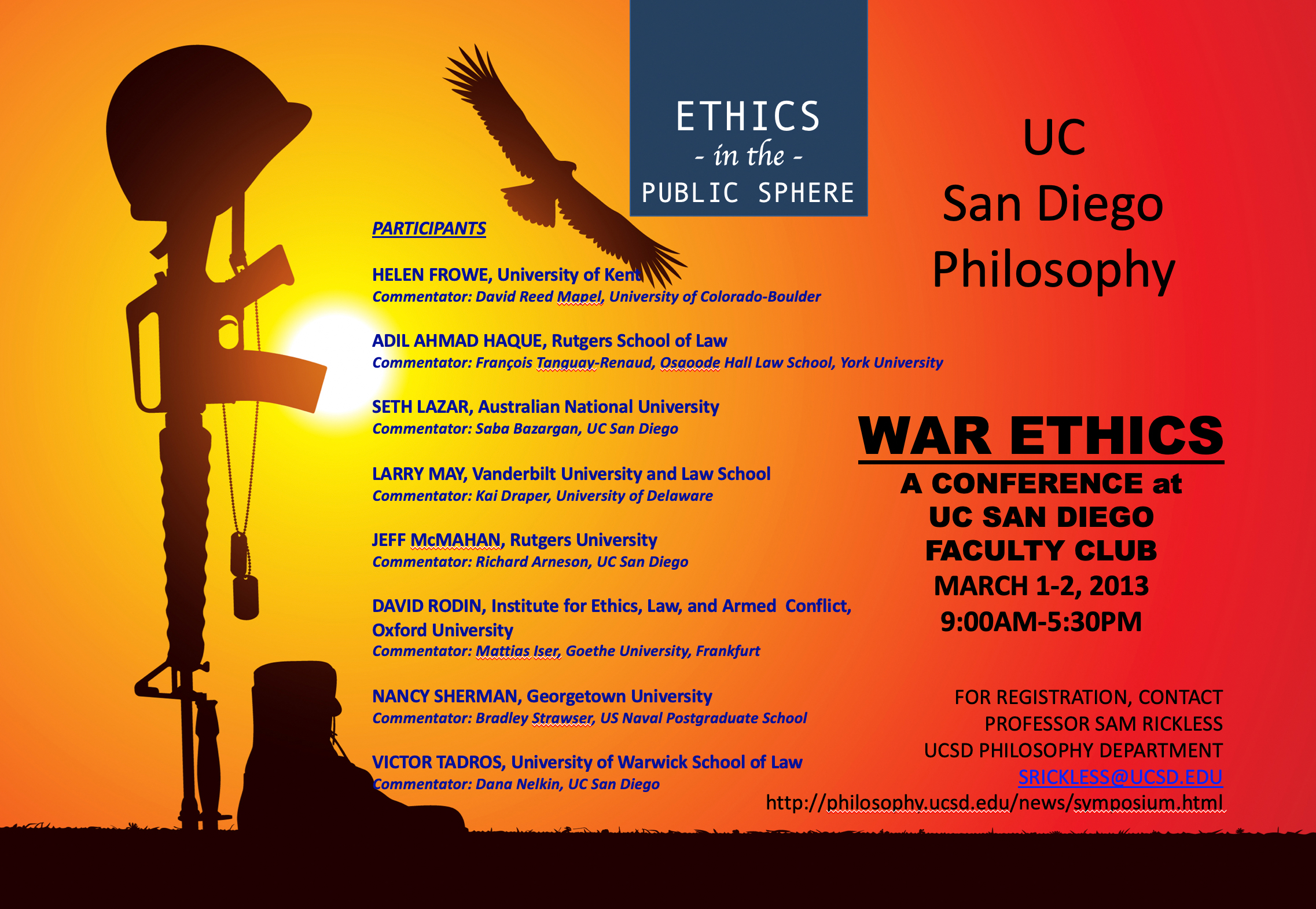

"War Ethics” - Symposium at the UCSD Faculty Club

"War Ethics” - Symposium at the UCSD Faculty Club

Introduction by Donald Rutherford & Sam Rickless

Participants (Click participant names to view their presentation)

- Seth Lazar - "War's Endings and the Structure of Just War Theory"

- Saba Bazargan - Commenting on Seth Lazar's presentation.

- Seth Lazar - Response and Q&A for "War's Endings and the Structure of Just War Theory"

- Helen Frowe - "Resisting Conditional Force"

- David Reed Mapel - Commenting on Helen Frowe's presentation.

- Helen Frowe - Response and Q&A for "Resisting Conditional Force"

- Jeff McMahan - "The Relevance to Proportionality of the Number of Aggressors"

- Richard Arneson - Commenting on Jeff McMahan's presentation.

- Jeff McMahan - Response and Q&A for "The Relevance to Proportionality of the Number of Aggressors"

- Larry May - "Human Rights, Proportionality, and the Rights of Soldiers"

- Larry May - Response and Q&A for "Human Rights, Proportionality, and the Rights of Soldiers"

- Adil Ahmad Haque - "Killing with Discrimination"

- Francois Tanguay-Renaud - Comment on Adil Haque's presentation.

- Adil Ahmad Haque - Response and Q&A for "Killing with Discrimination"

- Victor Tadros - "Duress and Duty"

- Dana Kay Nelkin - Commenting on Victor Tadros's presentation.

- Victor Tadros - Response and Q&A for "Duress and Duty"

- David Rodin - "Rethinking Responsibility to Protect"

- Mattias Iser - Commenting on David Rodin's presentation.

- David Rodin - Response and Q&A for "Rethinking Responsibility to Protect"

- Nancy Sherman - "Recovering Lost Goodness: Shame, Guilt, and Self-Empathy"

- Bradley Strawser - Commenting on Nancy Sherman's presentation.

- Nancy Sherman - Response and Q&A for "Recovering Lost Goodness: Shame, Guilt, and Self-Empathy"

"Aims of Education” - Symposium at the UCSD Faculty Club

Peter Singer. Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics, Princeton University.

Introduction by Donald Rutherford and Michael Tiboris

Participants (Click participant names to view their presentation)

- Jennifer Morton - "Revising the Aims of Education

- Jennifer Morton - Q&A for "Revising the Aims of Education

- John Johnson - "Education in Human Values"

- John Johnson - Q&A for "Education in Human Values"

- Dan Lang - "Making Meaning Out of the School Day"

- Dan Lang - Q&A for "Making Meaning Out of the School Day"

- Michael Tiboris - "What's Wrong with Undermatching? Personal Autonomy in Post-Secondary Matching"

- Michael Tiboris - Q&A for "What's Wrong with Undermatching? Personal Autonomy in Post-Secondary Matching"

“OUR DUTIES TO DISTANT NEEDY PERSONS” - Symposium at the UCSD Faculty Club

- “Fortune and Fairness in Global Economic Life" - Aaron James , Professor of Philosophy, UC Irvine. Commentator: Richard Arneson, Professor of Philosophy, UC San Diego.

- “Reconsidering Singer’s Drowning Child Example” - Douglas Portmore, Professor of Philosophy, Arizona State University. Commentator: K. Violet McKeon, UC Irvine.